STATE OF THE GREAT BARRIER REEF

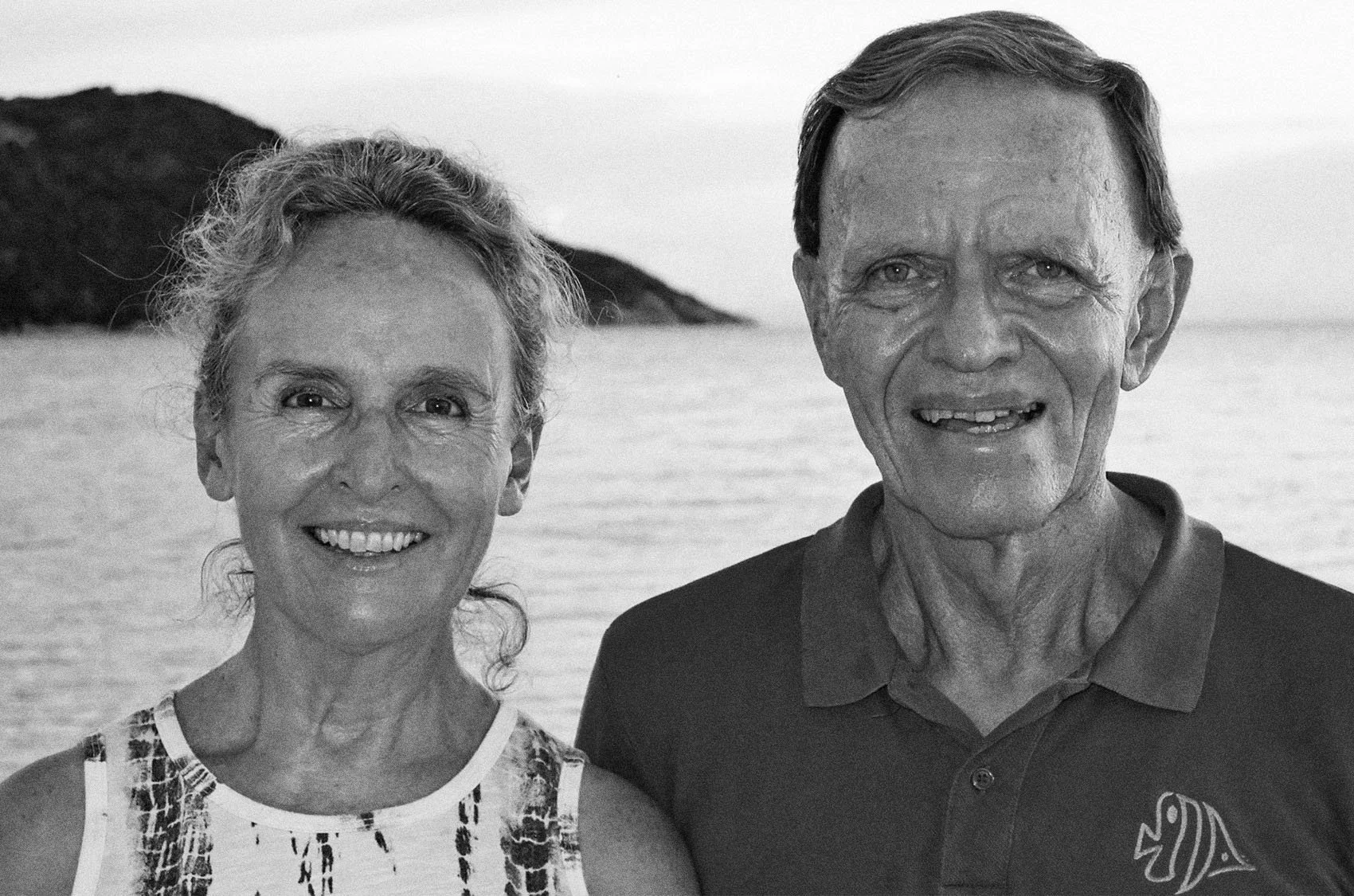

HAVING LIVED ON LIZARD ISLAND FOR OVER 30 YEARS, CORAL REEF SCIENTIST

DR ANNE HOGGETT UPDATES US ON THE FUTURE PROSPECTS OF THE WORLD’S LARGEST REEF

In Australia, Clean Waves focuses on protecting one of the world’s most vital ecosystems, the Great Barrier Reef. After collaborating on retrieving a ghost net from its outer fringes, we caught up with Lizard Island’s resident coral reef expert, Dr Anne Hoggett of the Lizard Island Research Station, to learn more about island life and how climate change is impacting the world’s largest reef.

“Coral reef science only started in the 1960s, so there’s an extraordinary amount to learn. We’ve only just scratched the surface.”

HOW DID YOU COME TO LIVE AND WORK ON A BEAUTIFUL ISLAND IN THE GREAT BARRIER REEF?

Well, my husband Lyle Vale and I have been the directors of the Lizard Island Research Station in the Northern Great Barrier Reef for 33 years this year. We used to work as taxonomists at the Australian Museum – the research station is run by the Australian Museum – and we fell in love with this place when we first visited in 1982. So we pulled out all the stops to get the jobs way back in 1990, intending to come for five years, and here we still are 33 years later.

THAT'S QUITE A LONG TIME TO HAVE SPENT ON SUCH A REMOTE ISLAND – WHAT IS LIFE LIKE THERE?

Oh, life is rather wonderful here. It’s an incredibly beautiful island, and if you love snorkeling and diving, clean white sand and beautiful clear water, this really is heaven. It's just wonderful – and of course, the work that we do here is very important. We do about a hundred different projects a year here with scientists from all over the world, and what we learn here at Lizard Island about how coral reefs work is published in scientific journals and forms the basis for the management of coral reefs.

“Those four years had changed a vibrant, beautiful coral reef into a moonscape – we had never seen anything like it”

WHAT ARE SOME OF YOUR FAVORITE SITES ABOVE AND BELOW THE WATERS OF LIZARD ISLAND?

People often ask that question and I'm not really gonna give you a good answer because I love the whole lot. It's very beautiful everywhere under and up above the water. It's not a tiny island; it's seven square kilometers in size, big enough to have a mountain a thousand feet tall on it. It's not the quintessential tropical island – it doesn't look like somewhere in Tahiti or the Maldives where there's big palm trees looping over the lagoon. It's quite dramatic looking. It's made of very old granite, and it can be quite dry in the dry season, but the rocks are just beautiful and it's got a really stark beauty.

WHAT DID YOU MAKE OF THE UN’S RECENT REPORT LISTING THE GREAT BARRIER REEF IN DANGER FROM RISING WATER TEMPERATURES, AND A DECLINE IN WATER QUALITY DUE TO AGRICULTURAL RUNOFF AND PLASTIC POLLUTION?

Well, I've got nearly 40 years experience at this one place, and in most of those years it’s been pretty stable – stably dynamic, as sometimes they'd have something happen to them like a cyclone or an outbreak of crown-of-thorns starfish, and they do recover from those reasonably quickly. In 2014 we had a massive cyclone that removed all the delicate corals from the entire perimeter of the Lizard Island group, and this was followed just 11 months later by a second massive cyclone that took off what little there was remaining. But as the Lizard Island group is made up of three or four little islands, we have a lagoon which managed to protect some of the corals from the big waves. But, in 2016 we had massive coral bleaching that was part of a worldwide event, and the little coral we had left in the lagoon were killed by the elevated temperatures. Then in 2017, the temperatures were as high as in 2016, but there was nothing left to kill here by that stage. It was comprehensive. Those four years had changed a vibrant, beautiful coral reef into a moonscape – we had never seen anything like it. It was just appalling, and I honestly never thought that I would see the corals recover in my remaining time here. But they have; now, six years later, some of those places now are every bit as good as they have ever been. It is a testament to the resilience of coral reefs and how they're able to recover from massive disasters.

THAT’S INCREDIBLE TO HEAR HOW QUICKLY THE CORALS RECOVERED. MOST PEOPLE WOULD THINK IT TAKES MILLENNIA FOR A HEALTHY REEF TO GROW.

Corals are able to recover very quickly. In fact, the beautiful corals, the ones that everybody thinks of when you think of a coral reef – the table corals and the branching corals – actually grow really quickly, and scientists call them ‘The Weeds of the Reef’. If you tell people that corals bounce back, they think what are we worried about? But the fact is, the trajectory is not right; it is going to happen again, and with increasing frequency. Really, my long-term outlook for coral reefs over the next, five, six decades to the end of the century is not being positive at all.

LET’S TALK A BIT MORE ABOUT THE POSITION OF LIZARD ISLAND IN THE NORTHERN GREAT BARRIER REEF, WHICH IS RIGHT IN THE PATH OF THE SOUTH EQUATORIAL CURRENT. HAVE YOU NOTICED AN INCREASE IN PLASTIC OVER THE FOUR DECADES YOU’VE SPENT ON LIZARD ISLAND?

It's dramatically increased. There are some beautiful beaches on Lizard Island that face the east with these headlands that stick out, almost welcoming the rubbish which pours in with open arms. Honestly, you can go there and pull off bags and bags and bags of this stuff, and then you go there three or four months later, and you wonder if you've ever been there. It just comes back so quickly. It's very depressing.

“There are some beautiful beaches on Lizard Island that face the east with these headlands that stick out, almost welcoming the rubbish with which pours in with open arms.”

YOU AND THE PARLEY AUSTRALIA TEAM RECENTLY COLLABORATED IN REMOVING A GHOST NET YOU'D FOUND OUT IN THE REEF – COULD YOU TELL US A LITTLE BIT MORE?

It was on the Outer Barrier Reef, which is about an hour on the boat from Lizard Island. A bunch of us were doing a drift dive in a very strong current in one of the narrow passages between these ribbon reefs that line the edge of the continental shelf – a very different environment to Lizard Island. We were just ripping along at a very high pace and I noticed a drift net at about 15 meters depth on the corner of one of these reefs and thought, oh dear, that's terrible. I didn't even have time to get a photograph of it before I was swept past. And so when Parley rang up a while ago and asked if we knew of any drift nets, I told them where it was and luckily they were there on a day where the current was not as strong and they were able to retrieve it, which was fantastic. They're horrible things: they just wrap around the corals and smother everything that lives.

YOU’VE SPENT NEARLY FOUR DECADES STUDYING CORAL. WHAT ARE SOME OF ITS MYSTERIES THAT KEEP YOU UP AT NIGHT?

Oh, there are so many. Coral reef science is really young, it only started in the 1960s. If you compare that with physics, going back to Newton, we are really young science, so there's an extraordinary amount still to learn. We've only just scratched the surface. Take the diversity of coral reefs: here at Lizard Island, we've got about 1,500 species of fish, and there are still new species of fish to be discovered and they're the big things. But think about the tiny, little things. To give you an example: we've got a group of parasitologists here at the moment who are looking at the internal parasites of fish. After a two-week trip here they'll describe 30 new species of parasite – worms, crustaceans, that sort of stuff. And they're everywhere. It really is a taxonomist dream, and we haven't got enough taxonomists to do the work that is necessary.

Photography Courtesy of: Lizard Island Reef Research Foundation, Christian Miller, The Ocean Agency